AI on Mobile Substitutes, AI on Desktop Multiplies

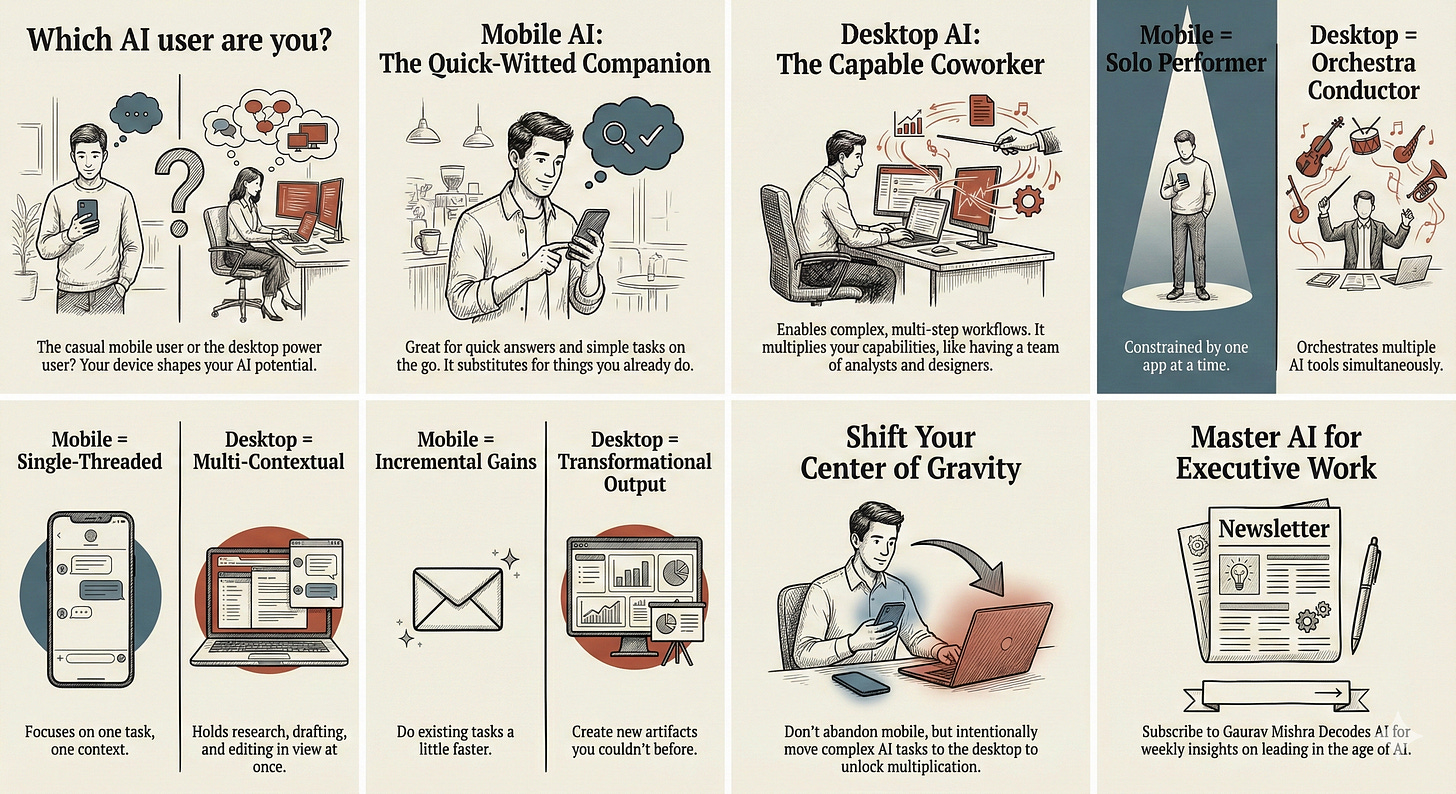

Do you think of AI as a quick-witted companion or a capable coworker?

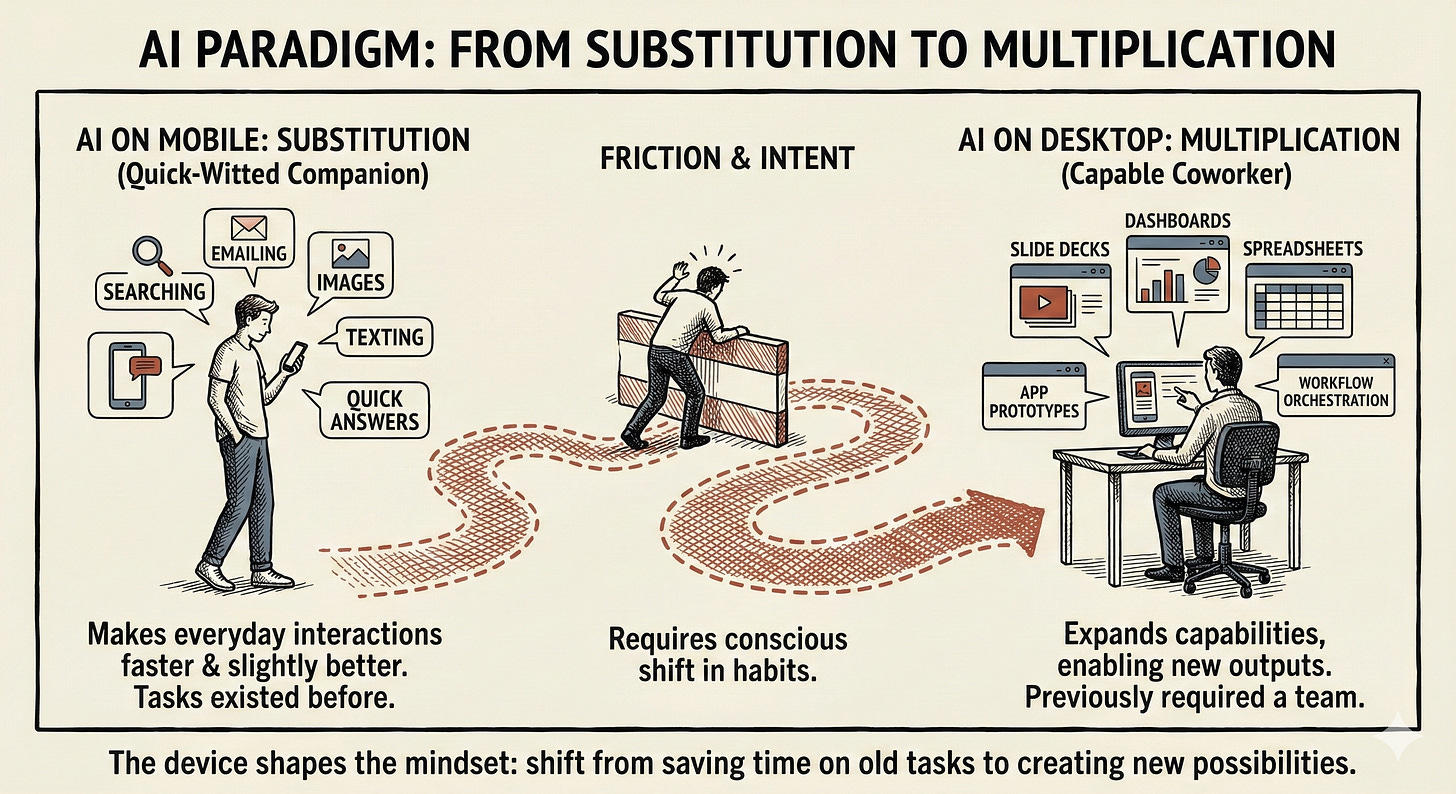

AI on mobile mostly substitutes for things we already do on phones (searching, emailing, texting), while AI on desktop adds capabilities that used to require other people (analysts, designers, developers).

This device split might create two distinct user populations with different intuitions about what AI fundamentally is. The 5% who pay for AI are likely to be the desktop users who have discovered multiplication rather than substitution.

As we spend more time with AI products, our device preferences might change. The mobile phone might get squeezed from one side by the laptop and from the other side by AI wearable devices.

I’ve observed that I increasingly use AI on mobile and desktop in different ways, to accomplish different tasks. Counterintuitively, the desktop browser has become my primary mode for using AI, rather than the mobile app.

The friction on mobile. Last week I tried to force ChatGPT into slow, deliberate reasoning on my iPhone, to transform a meeting transcript into a memo. It kept snapping back to “good enough,” even when I asked for step-by-step thinking. When I ran the same prompt on my MacBook, with extended thinking on, the interaction felt more controllable and more serious. ChatGPT seemed to expect me to create real work on the desktop browser, not on the mobile app.

Devices shape experiences. I pull out my phone when I am on the move, between meetings at work, or hanging out with my cats at home. The phone signals a break from both work and play, a moment to catch up on messages on WhatsApp, podcasts on Snipd, and articles on Readwise Reader. When I sit down at a desk, open my laptop, and ask Raycast to snap three apps on the screen, I am signaling to myself that I am ready to work. The AI products themselves behave differently on mobile and desktop, reinforcing my instincts into habits.

The return of the desktop. This device split I have noticed runs counter to what the last two decades of technological evolution has trained us to expect. We have built our digital lives around the assumption that the phone would eventually replace the desktop as our default computer. Social interactions, entertainment, and commerce are all mobile-first by default. But AI is not following that script. As we spend more time with AI products, the center of gravity might be shifting from mobile to desktop, and from apps to browsers. The reasons for this shift reveal something essential about how we work and create.

Substitution on Phones, Multiplication on Desktop

The substitution-multiplication distinction I am drawing is simple but clarifying. Think of it like the difference between a quick-witted companion and a capable coworker.

Substitution on mobile. A quick-witted companion makes everyday interactions more enjoyable. They help navigate a conversation, find an answer, or pass the time on a commute. But they do not change what we can create or accomplish. When I use AI on my phone to get a quick answer, draft a simple email, or transcribe a voice memo, I am using AI for substitution. The task existed before. I am simply completing it faster with slightly better results.

Multiplication on desktop. A capable coworker expands what we can attempt on our own. They help us create outputs that were not in our repertoire at all. When I use Gamma to create a slide deck, Gemini to build a dashboard, Claude to design a spreadsheet, or Lovable to generate a working app prototype, I am not substituting for something I used to do myself. I am using AI for multiplication, to do things that previously required a team with specialized skills: a researcher, an analyst, a designer, a developer.

Habits shape intuition. Our defaults for where we use AI and for what matters because we are in the early years of learning what AI is for. The device we use shapes what we ask from AI. What we ask AI shapes what we learn about AI’s capabilities. What we learn about what AI can do shapes our intuitions about what is possible with AI. If we spend these formative years treating AI as a quick-answer substitution machine, we may never discover its multiplicative possibilities when we ask it to co-create with us.

Why the Desktop Enables Multiplication

There are behavioral and technological reasons why AI on desktop enables a multiplication of our repertoire, while AI on mobile merely makes tasks a little better, a little faster.

Visual space enables complexity. The deeper reason why the desktop enables work is not screen size alone, but working memory. On my laptop, I can have my fact sheet in Perplexity, my research in NotebookLM, my notes in Obsidian, my draft in Claude, a meeting transcript in Otter, a related email thread in Outlook, and the final edit in ChatGPT Canvas open in different windows. I can snap multiple windows on the screen at the same time, to see comparisons, visualize relationships, sense patterns.

Multi-tasking enables workflow. I can also see multiple windows at the same time on my iPad, but when I need to shift into creation mode, I turn to my MacBook (with my iPad as a second screen). On my laptop, I can toggle between windows, paste a snippet from Raycast, use Wispr Flow to talk to a text box, use a browser extension to save a new tool I discovered for later, and iterate on the final output. Each device, each AI product becomes an instrument in an orchestra, and I feel like I am the conductor.

AI browsers eliminate friction. The rise of AI browsers like ChatGPT Atlas, Perplexity Comet, and Dia makes this orchestration even more powerful, directly from the AI sidebar. Now, instead of toggling between windows, I switch between tabs as the AI in the sidebar understands the ask from an email thread, summarizes the decisions from a meeting transcript, and gives feedback on a memo or a slide deck. These browsers are desktop-first by design, built for the kind of multitasking that phones or tablets cannot yet fully support.

Experiences calibrate expectations. On my phone, I feel like a solo performer, restricted to one app at a time. There is no orchestra to conduct, no instruments to balance, no way to hold multiple threads of work in view at once. The environment constrains what I think to ask. When I know I cannot compare two drafts or pull in context from two different apps, I stop asking for things that would require those moves. Over time, I stop imagining the fuller arrangement that desktop makes possible.

The Data Confirms the Desktop-Mobile Split

The emerging substitution-versus-multiplication split in mobile and desktop use of AI shows up in the data, with interesting implications.

Website referrals from AI. A BrightEdge analysis found that more than 90% of AI search referrals come from desktop across ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Gemini. This is the opposite of Google search, which skews mobile. This skew shows that desktop use aligns with research-heavy tasks, while mobile favors casual browsing or discovery. The data also reflects product quirks: AI overviews appear more often on desktop while mobile AI apps often require a second click from in-app previews to reach external links.

Productivity versus expression. The Andreessen Horowitz list of the top 100 Gen AI consumer apps has a clear split between depth versus immediacy: web usage leans more productivity-driven, while mobile usage leans more expression-driven. On the web list, many top entries support longer sessions for writing, research, coding, and building durable work artifacts. On the mobile list, many top entries focus on photo and video editing, filters, avatars, translation, and quick utility actions. General AI assistants appear on both lists, but they sit among different neighbors, which shapes how people use them.

Desktop users likely to pay. ChatGPT has 800-900 million weekly active users as of late 2025, according to OpenAI, but only 20-30% use the product daily, and less than 5% pay (Benedict Evans). The free users asking quick questions are likely overrepresented on mobile. The paid users running multi-step tasks to create artifacts are likely overrepresented on desktop. Our default device not only shapes our use of AI, but also propensity to pay for AI.

Product design dynamics. Three product design dynamics reinforce the mobile-desktop split. Because mobile users expect simple interfaces and quick answers, mobile AI apps hide advanced functionality and skew auto-routing towards faster models. The constraints around compute and costs make this auto-routing behavior even more important for AI platforms, especially for ChatGPT and Gemini, which have large mobile-skewing free consumer users. Finally, some advanced features and interfaces simply do not translate to the smaller mobile screens.

Will the Mobile Phone Remain Dominant?

Another data point hints at something shifting beneath the surface. Over the past decade, the ratio of iPhone to MacBook unit sales has held remarkably steady at roughly ten to one. But in recent quarters, MacBook growth has outpaced iPhone growth, sometimes significantly.

Device upgrade cycles. I notice this shift in my own Apple device upgrade calculus. My iPhone 13 Pro Max is starting to show its age. The battery drains faster, and the camera lags behind newer models, but it does not feel old because of AI. My MacBook Pro M2 works well enough with Outlook, Office, and Teams, but struggles with AI browsers and always-on ambient AI assistants. The machine that felt future-proof in 2023 now feels like a slow coworker who is still showing up to work like it is early 2020.

Phones getting compressed. I find myself wondering whether the iPhone is getting compressed between desktops, tablets, and wearables. The MacBook is becoming more essential for the kind of AI work that creates real artifacts. The iPad is an excellent device for reading, gaming, and watching videos. AI-native wearable devices like Ray-Ban Meta sunglasses, Plaud, and Limitless are emerging as ambient capture tools. Perhaps the future of the phone lies in its foldable hybrid phone-tablet avatar. I am definitely waiting for Apple’s folding iPhone (and real Apple Intelligence) before I upgrade my iPhone.

The mobile counterargument. Three developments could close the gap between we can do with AI on the phone and the desktop. Voice and multimodal interfaces might eliminate the keyboard advantage if AI can execute complex spoken instructions reliably. AI agents running in the background could shift value from interactive sessions to ambient automation. And as compute costs drop, the product design incentive to steer mobile users toward shallow responses will weaken.

The limitations of voice. I take this counterargument seriously, particularly the increasing importance of voice. Voice has become a critical part of my own workflow, both on the input voice-to-text side and the output text-to-voice side. With Wispr Flow, Otter, and Granola, voice transcription has largely replaced typing for me. I am increasingly consuming text on-the-go in voice mode, including in NotebookLM. Counterintuitively, many of these voice AI tools either require the desktop or work better on the desktop. Voice input is only the first step. Steps two to ten that get us from voice input to a finished artifact still require a desktop.

A Daily Practice to Shift From Substitution to Multiplication

I get the attraction of staying in lean-back, mobile-first, substitution mode. But I believe the executives who carve out even one hour per week for multiplication experiments will compound an advantage their peers cannot easily replicate.

Substitution mode is easy. The strongest case for staying in mobile-heavy substitution mode with AI is entirely practical. Using M365 Copilot to draft an email, using ChatGPT to quickly search for an answer, or using Gemini to edit an image is easy. For busy executives, time to experiment is scarce, learning new workflows has friction, and change fatigue is real. Most executives spend their workweek answering emails, reviewing documents, and participating in meetings. The empty chat box doesn’t make it obvious how it can help or what else we might do with it.

Multiplication mode needs intent. Learning to see AI not only as a quick-witted companion but as a team of capable coworkers requires intent. Over time, I have intentionally developed the practice of observing my own behavioral patterns and asking what it represents. If we do this consciously, we will cultivate an intuitive feel for the limits of what’s possible with different AI products, in different workflows, on different devices.

My own daily practice. Whenever I find myself giving AI a short, unstructured prompt, I ask myself why. With Wispr Flow transcription, Raycast snippets, and prompt generator Custom GPTs, transcribing my thoughts into a prompt has become almost instantaneous. I have learned by experience that a longer, more structured prompt with a longer thinking window will always get me to the final artifact faster. I find that sometimes I do genuinely need a quick answer, but more often, I simply succumb to the default fast chat mode on the mobile app, only to do more rework later.

Three experiments to test patterns. I would invite you to test your own patterns with a few small experiments this week. First, notice when you abandon an AI task on mobile and switch to desktop and reflect on the friction that made you switch. Second, try building one artifact like a three-page memo entirely on mobile and notice where the environment fights back. Third, ask your colleagues or team members what is the most complex task they have tried with AI. The answers will reveal where you and your teams sit on the substitution-to-multiplication spectrum.

I am curious about the frictions you face using AI on your phone. What tasks do you start with AI on mobile and then abandon? What makes you reach for your laptop instead? Hit reply and share what you have noticed. Your experience might reveal a pattern I have missed.

I’ve always used AI on my phone even when I’m actively working with my laptop open in front of me . Airdrop helps me share docs from phone to computer with ease . This has encouraged me to start experimenting with using computer for serious work tasks :)