The AI Jigsaw Frontier

AI Jigsaw Frontier is the practice of assembling AI products like puzzle pieces to even out the jaggedness of the AI frontier

My AI product stack in early 2026 increasingly looks like a messy jigsaw puzzle.

Claude Cowork is the keystone in my jigsaw, but it is only one piece. I start most thinking and writing tasks in Claude Cowork, then save the output as Markdown files in my Obsidian vault or GitHub repository. I bring in context via deep research from Gemini, meeting transcripts from Granola, voice notes from Wispr Flow, and highlights from Readwise Reader. Once a draft is done, I ask Cowork to create a prompt for Nano Banana Pro, then create the visual artifacts in Gemini, Google Slides, NotebookLM, or Manus. If I need to work with spreadsheets or presentations, I switch to Claude in Excel and PowerPoint. What’s missing in my AI puzzle is how most people use AI: back-and-forth conversations with an AI chatbot, even Claude Chat.

On good days, I think of my AI jigsaw as the epitome of system design. Each piece in the jigsaw is genuinely good at the task assigned to it and my workflow would break if I removed a tool. The switching cost between tools is real, but so is the satisfaction of designing a system that is more than the sum of its parts.

On bad days, I think of the AI products in my jigsaw as a clowder of unruly house cats. The cats run around, break things, get in the way, and cannot be tamed. But they follow me around like puppies, purr on my lap when I pet them, and conjure unexpected moments of delight on demand. I’m always annoyed by them, but I cannot do without them.

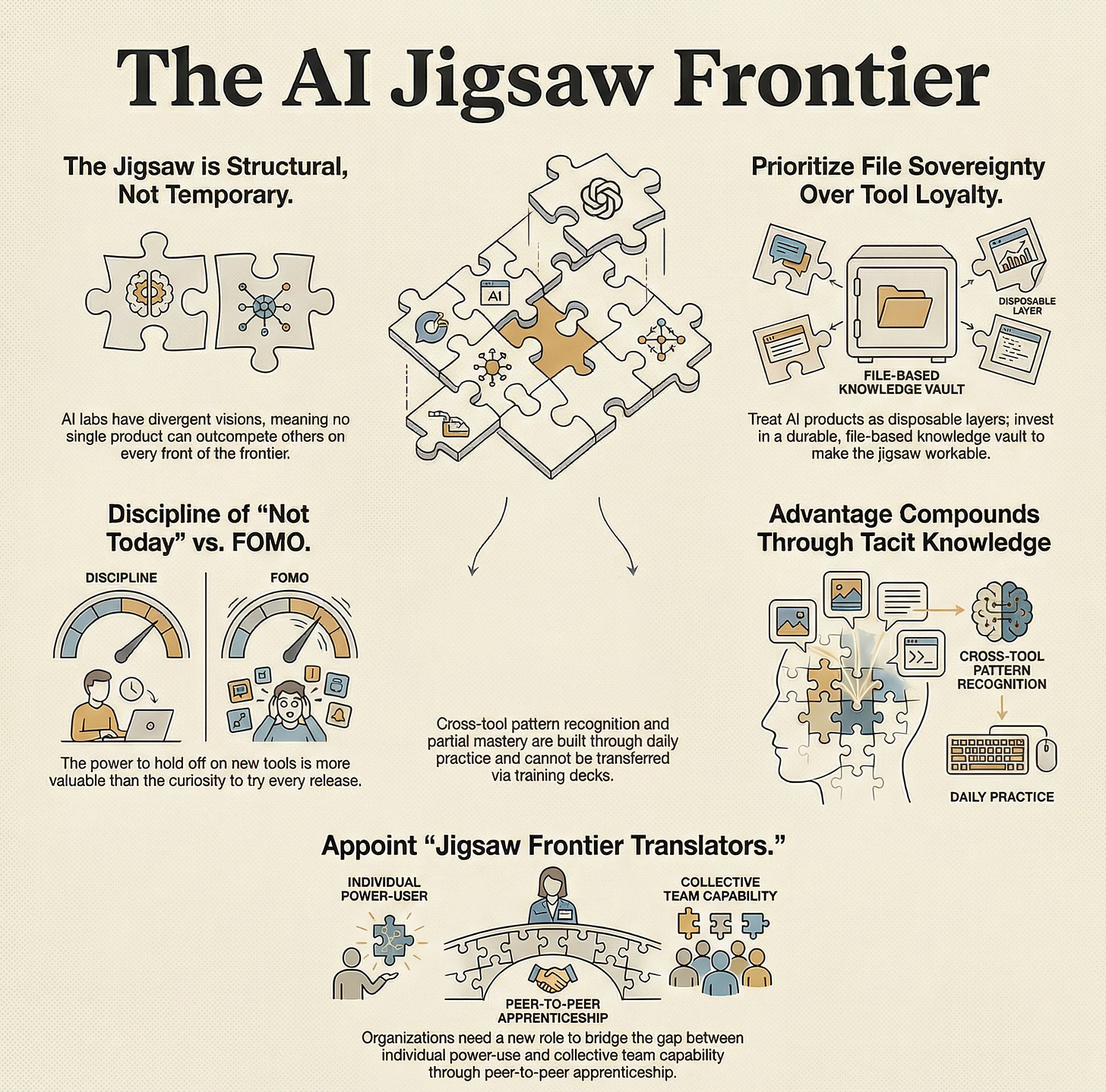

The AI Jigsaw Frontier is Both Structural and Personal

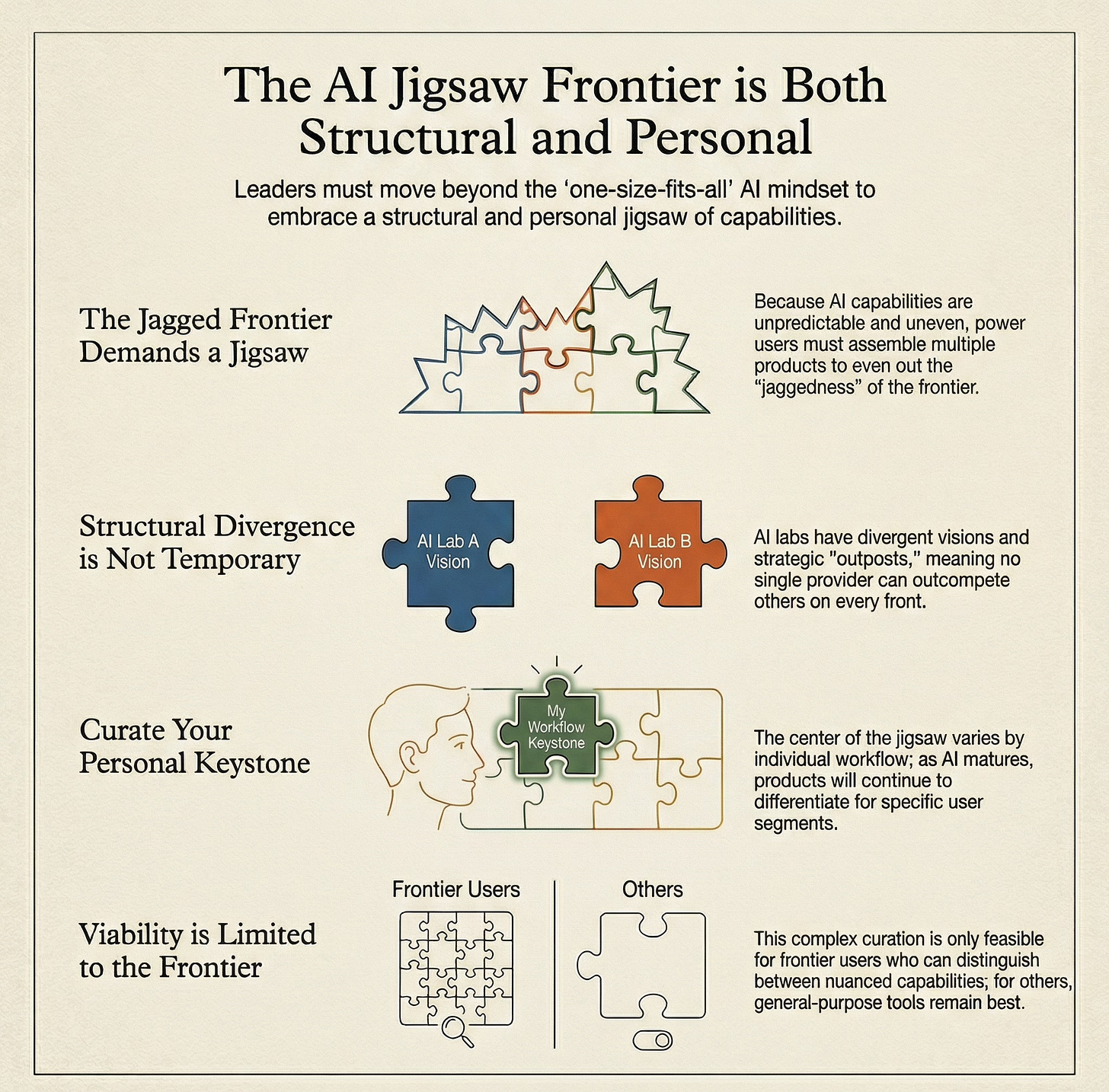

Ethan Mollick’s ‘Jagged Frontier’ concept describes the unpredictable and uneven boundary of AI capabilities. AI excels at some complex tasks while failing at seemingly simpler ones. This makes it difficult to intuitively know what AI can or cannot do. AI is inscrutable and unpredictable, like cats.

Power users at AI’s jagged frontier can no longer choose one AI product and expect it to be good at everything we do. We need to assemble AI products like puzzle pieces in a jigsaw that fits our own use cases and workflows. I call the practice of assembling AI products like puzzle pieces to even out the jaggedness of the AI frontier the ”AI Jigsaw Frontier”.

The AI Jigsaw Frontier name is deliberate. This curation of AI products is only desirable, viable, and feasible for power users at the frontier of AI. Only frontier AI users can distinguish between the capabilities of different AI products, use them fully, and justify paying for them. For everyone else, the best approach continues to be to use one general-purpose AI product like Gemini or ChatGPT for all their tasks.

The AI Jigsaw Frontier is structural, not temporary. It exists because the AI labs building the pieces have divergent visions for the value AI will create and capture. None of them can outcompete others on all the fronts of the AI frontier; therefore, each of them has picked their own outpost.

Google chose multimodal intelligence because it needs to build upon its dominance in Google Search and YouTube. xAI chose real-time search and AI companions because it needs to design for the preferences of heavy X users. OpenAI chose breadth because it needs to challenge Big Tech incumbents on the core business models of search, advertising, commerce, and devices. Anthropic chose code as the underlying layer for all knowledge work because it wants to primarily target professional and enterprise users.

The AI jigsaw is also personal. Claude is the keystone of my AI jigsaw because it fits most neatly into my use cases and workflows. But Claude does not do images, videos, or voice. If your use case is social media short videos, Claude will not be the keystone in your AI jigsaw.

As AI matures, AI products will continue to differentiate to appeal to different segments of users. The range of power user use cases and their preferences for harnesses that fit the quirks of their workflows will grow. The number of pieces in the AI jigsaw and the number of ways to combine them will increase exponentially.

The AI Jigsaw Frontier Makes AI Products Disposable

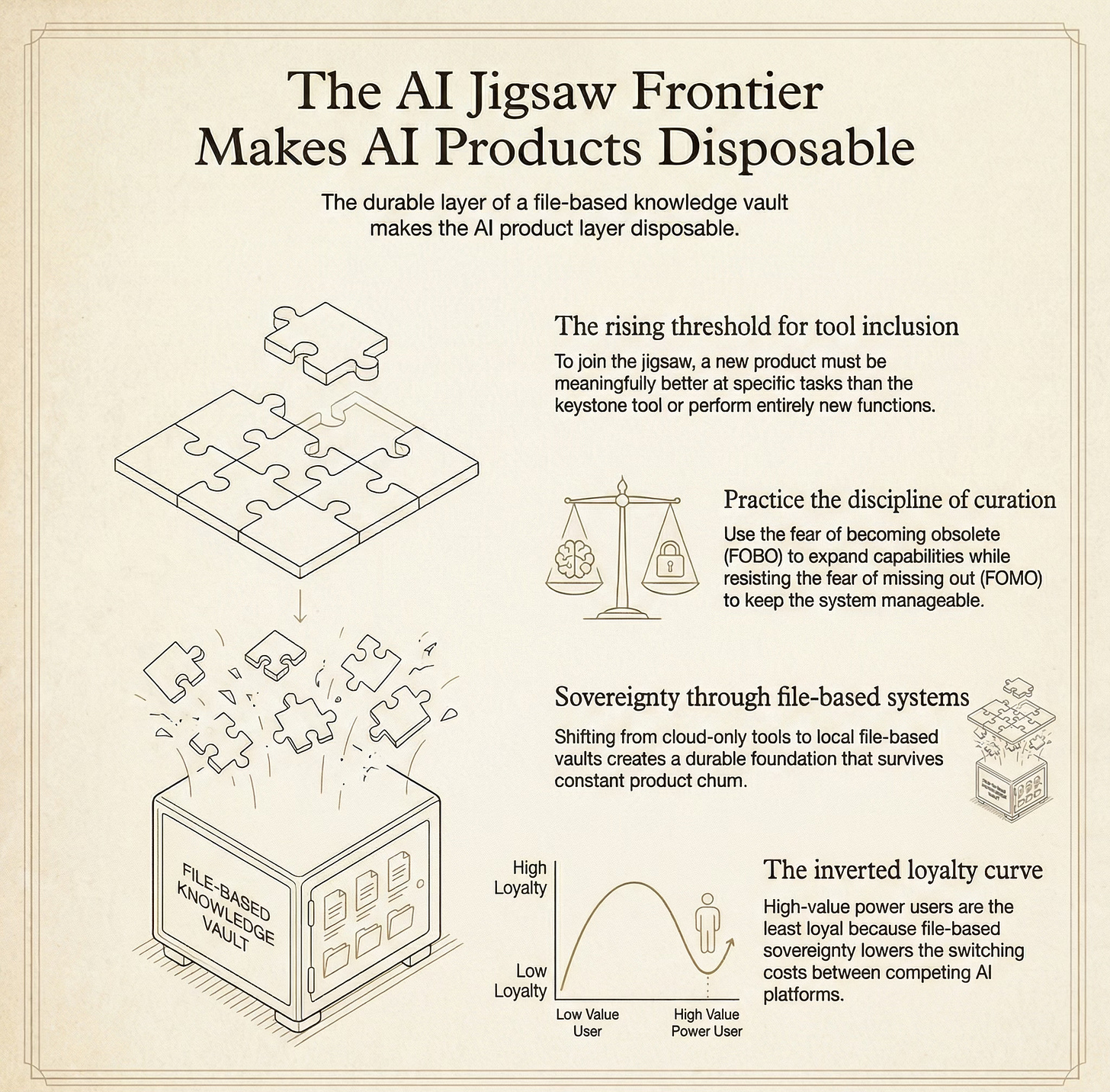

To become a part of my AI Jigsaw, a new product must be meaningfully better at specific tasks than Claude’s portfolio of products, or do entirely new tasks. As general-purpose AI products are becoming better, the bar for genuine new value is rising for specialist AI products.

As an example, Nano Banana Pro in Gemini creates stunning infographics as images, but I cannot use it within Gemini Canvas to create slide decks. While writing this essay, I discovered that I can create creates slides and infographics in Google Slides, but not the full presentation at once. NotebookLM can quickly create infographics and PDF slide decks from deep research, but I cannot iterate on them. Manus can edit the Nano Banana Pro infographics in slide decks, but takes more time and costs more in credits.

Each product earns its place depending on the trade-off between precision, time, and cost. It is inevitable that Google will make it easy to edit Nano Banana Pro infographics and slide decks, which will make Manus redundant for me.

This churn in the pieces of my AI jigsaw is constant. Deep research in Gemini and ChatGPT, wide research in Manus, and real-time social search in Grok have made Perplexity redundant for me for fact-checking.

The rising threshold for inclusion in the AI jigsaw matters because it keeps the jigsaw manageable. Without it, every new tool demands a subscription and a learning curve, and curating the portfolio of AI tools becomes its own full-time job. The curiosity to find out whether a new tool changes what’s possible is important. The discipline to hold off integrating it into our AI jigsaw is even more important. FOBO (fear of becoming obsolete) drives us to learn tools that genuinely expand what we can do. FOMO (fear of missing out) tempts us to chase every new release.

I no longer take annual subscriptions for AI products, even if they’re giving me 20% off. I only take monthly subscriptions because $20/month subscriptions that I use are better value than $200/year subscriptions that I don’t use. Half the AI tools we use today in our jigsaw will get replaced in a year, by a general-purpose keystone tool, or by another new or newly improved specialist tool.

Moving from working with AI tools in the cloud to getting AI tools to work with files on our desktop makes the jigsaw frontier workable. The file-based system solves for AI product limitations around memory, context, and continual learning. Investing in the durable layer of a file-based personal knowledge vault makes the AI product layer disposable.

It’s instructive that Anthropic has led the shift to file-based personal AI sovereignty. As the number three AI player, Anthropic’s incentive is to lower switching costs. OpenAI and Google suddenly find themselves in an inverted loyalty curve situation where power users who pay the most are also the least loyal.

The AI Jigsaw Frontier Creates More Work, Not Less

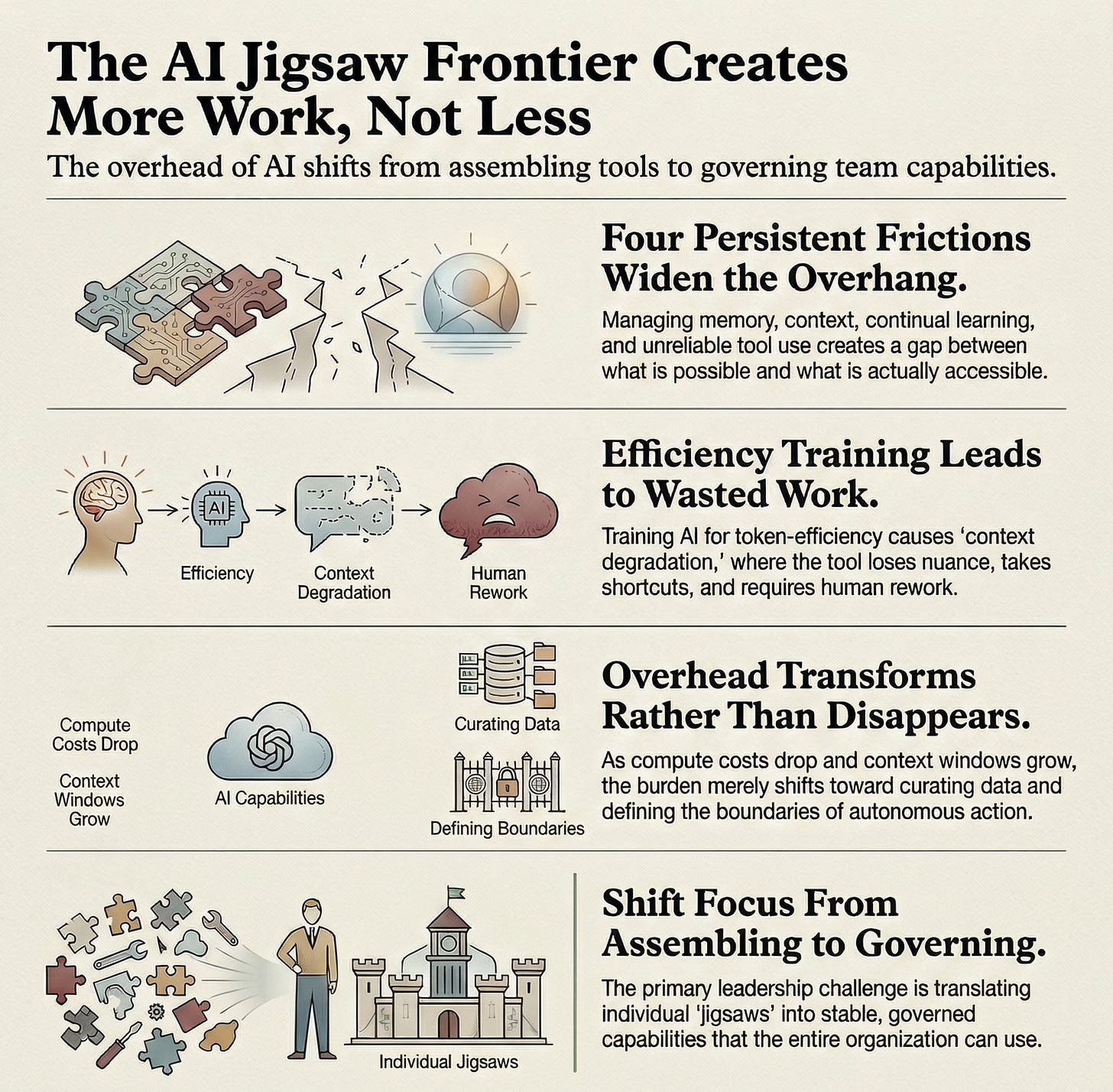

The file-based system makes the jigsaw workable, but it does not solve the persistent frictions underneath. These persistent unsolved frictions widen the AI overhang between what is possible and what is accessible for most of us.

At the beginning of every session, I need to point Cowork to the right files and skills so it understands both my context and my custom instructions. In the middle of each session, I need to anticipate Claude’s context degradation, close the session, and create handoff documents. After every session, I need to ask Cowork to create or update a skill to replicate what it has learned in the session.

If I am not careful, Cowork will lose its way in the middle of a task and start behaving like a sleep-deprived employee. It will forget aspects of the original ask, lose nuance in reasoning, and become prone to skimming, skipping, and taking shortcuts. It will make (the wrong) assumptions that lead to (the wrong) decisions that waste time and tokens. It’s ironic that the very training that forces AI tools to be token-efficient to save compute costs results in wasted work.

Constantly managing memory, context, and continual learning is hard work. What makes it harder still is that the entire system is all dependent on reliable tool use. Tool use is about AI acting on external systems: searching the web, reading files, calling APIs, using connectors. That boundary is where things inevitably break. The failure mode is not that tools don’t work. It is that tools work unreliably, and the AI does not know when it has failed.

All four frictions combine to create a uniquely frustrating experience when I sit down to write these long-form essays on the AI frontier. Opus 4.6 has a training data cutoff of May 2025, and it struggles to understand the AI landscape in February 2026. It has access to a search tool, but it refuses to proactively use it to update its context. It makes mistakes repeatedly, and the mistakes eat up the context window, before I have the chance to correct them. I cannot trust any changes Claude has made after it has hit compaction, so I need to spend an additional session to check its work.

A single essay can take a dozen 1 million token window sessions to finish, most of them spent on correcting Claude’s mistakes, and trying to stop it from making them again. Getting Claude to hold the full intent and meaning of the 2,500-word essay in its head and holistically suggest improvements in narrative flow, logical cohesion, and second- and third-order thinking feels like herding cats. Getting it to track the learnings across a dozen revisions and use them to update the essay review skill feels hopeless. On days like this, I wonder why I bother. It must be easier to write 2,500 words myself.

Then, I remind myself that working with AI is like living with cats. Just like it’s futile to shout at my cats, it’s futile to prompt AI in ALL CAPS. I have to give up the illusion that I can train it, I have to accept it as it is, and trust that wisdom and delight will follow, once the case of the zoomies has calmed down.

All four frictions trace back to constraints around compute cost, model training data cutoff, post-training alignment, and tool use. But even when all these constraints loosen, the hidden overhead transforms rather than disappears.

Cheaper compute means longer context windows, but we still need to curate what goes into that context. Architecture that supports continual learning means the AI can adapt, but we still need to review what it learned and correct the wrong lessons. Better alignment means smarter memory, but we still need to decide what the AI should remember and what it should forget. Better tool use means more capability, but we still need to define when AI should act autonomously and when it should ask before taking action.

The overhead shifts from assembling the AI jigsaw to governing it and translating it into capabilities that the entire team can use. When we go from one AI product to the AI jigsaw, and from personal use to the team use, the overheads multiply.

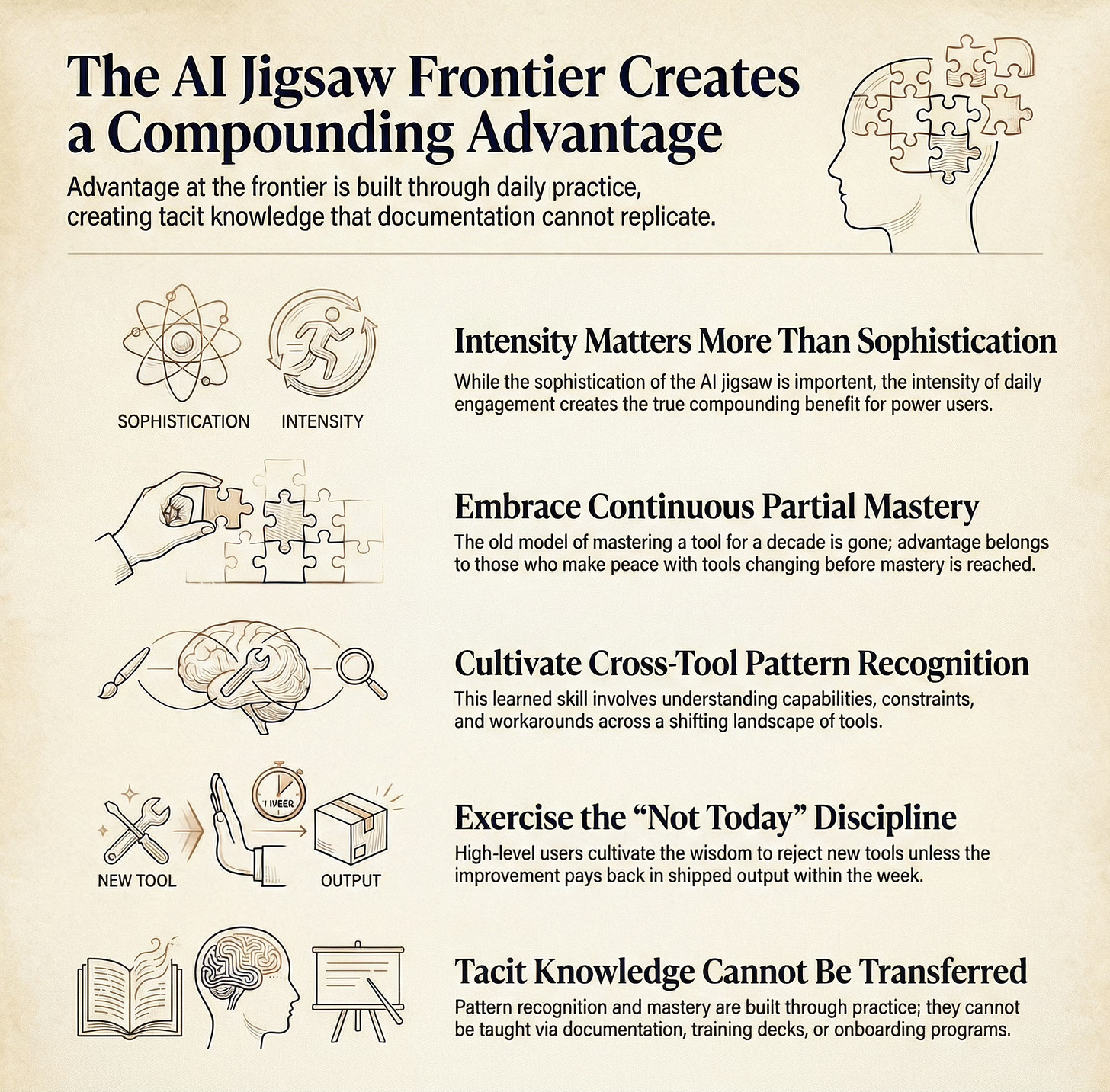

The AI Jigsaw Frontier Creates a Compounding Advantage

For most of us, this overhead is not worth it, and the right approach is to use one general-purpose AI tool every day as a thinking partner. The need for an AI jigsaw arrives when the single AI tool hits a ceiling. The limitations around memory, context windows, and continual learning become visible only through sustained use. That is when assembling a personal AI jigsaw becomes a necessity.

Zooming out, the compounding benefit of AI use has two dimensions: the sophistication of the jigsaw and the intensity of engagement with it. A colleague who uses ChatGPT and Otter meeting notes every day to extract action items from meetings gets more compounding benefit than someone who is constantly switching between tools. Intensity of daily engagement with AI tools matters more than the sophistication of the AI jigsaw. Power users at the AI jigsaw frontier do both: we assemble the AI jigsaw and engage with it intensely everyday.

It takes daily practice with the AI jigsaw to even understand the constraints around memory, learning, context windows, and tool use. It takes daily tinkering to build workarounds for these constraints, or to recognize when a new solution removes one. Pattern recognition at the AI frontier is a learned skill, just like with physical jigsaw puzzles.

It is disorienting for frontier AI users to be in continuous partial mastery mode across all the tools in our AI jigsaw. The old model of learning, mastering, then applying for a decade is gone. The tools change before we reach mastery, and this shift threatens our professional identity. Once we make peace with continuous partial mastery, it provides a compounding advantage.

Frontier AI users need to be constantly vigilant that fine-tuning the system does not become the end instead of the means. Improving a workflow feels productive even when it is not shipping real work. Integrating a genuinely useful new product can push the overhead of fine-tuning over the edge into overwhelm. We cultivate the wisdom to know when to integrate a new tool into the jigsaw and when to say “not today”. We learn from experience that every improvement we make needs to pay back in shipped output within the week.

As an example, AI coding products are becoming useful for non-coding knowledge work. Pattern recognition helps us see that the skills and automations in the new Codex app are similar to the skills and plugins in Claude Cowork. Continuous partial mastery helps us quickly learn where Codex can add value beyond what Cowork can. The “not today” discipline helps us recognize that we still have value to unlock with Cowork before we experiment with Codex.

What cross-tool pattern recognition, continuous partial mastery, and the “not today” discipline share is that they are all forms of tacit knowledge. They can only be built through daily practice. They cannot be transferred through documentation, training decks, or onboarding programs.

People who are opting out of seriously using AI tools will eventually need to learn more than just the tools. They will also need the tacit knowledge that frontier users have built over months. This is the compounding advantage at the AI frontier and it is exactly what makes the next problem so hard.

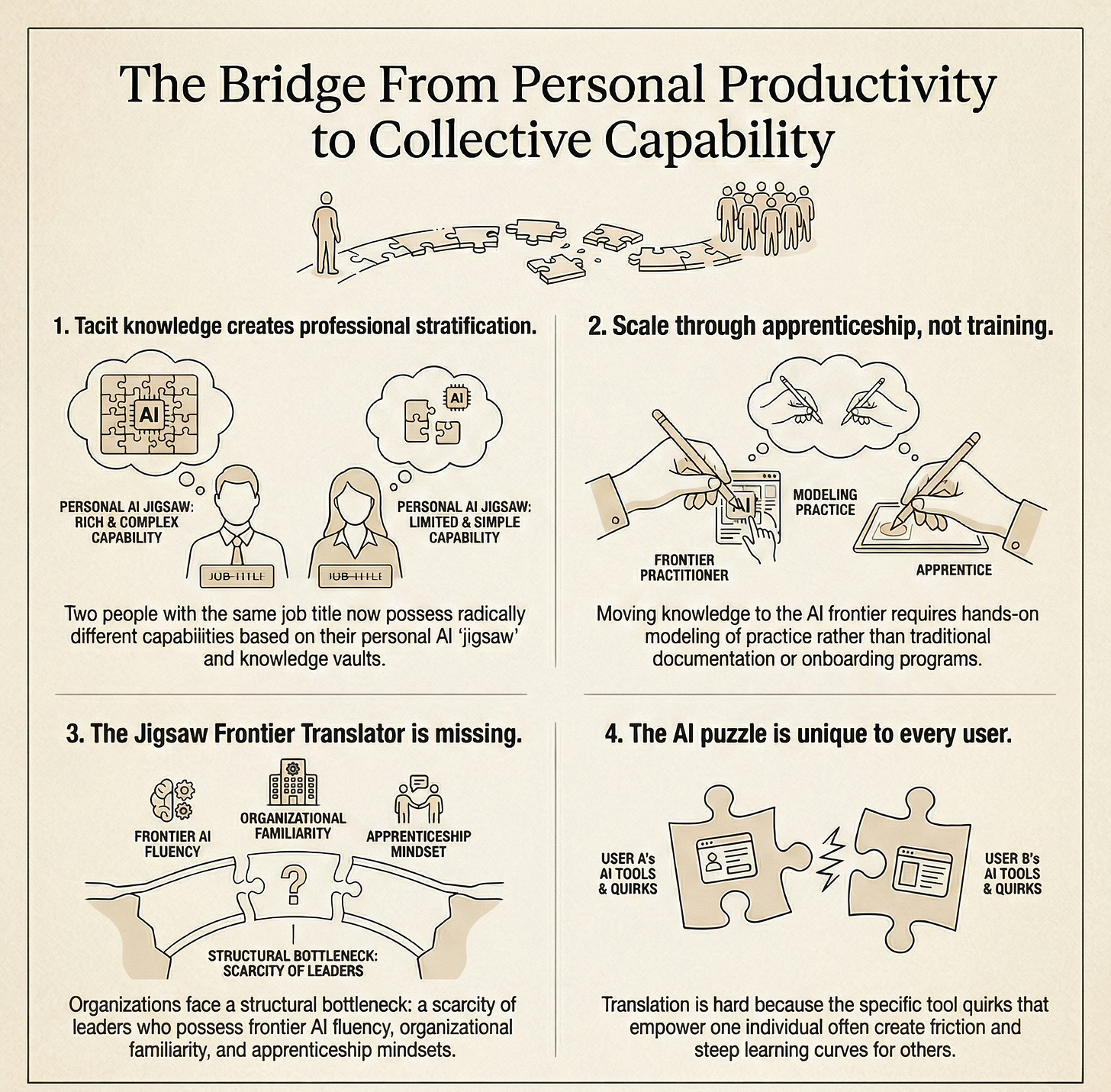

The Bridge From Personal Productivity to Collective Capability

The compounding advantage of the tacit knowledge creates a form of professional stratification. Two people with the same job title can have radically different AI capabilities based on whether they have assembled a personal AI jigsaw and built a personal knowledge vault.

It also means that organizations that want to operate at the AI frontier will need to find a way to translate and transfer this tacit knowledge. This tacit knowledge transfer will need something closer to apprenticeship than training.

In 2026, the most valuable AI practitioners will not only assemble the AI jigsaw for themselves but also translate it for their teams and organizations. The practitioner who can bridge the AI jigsaw from individual practice to organizational capability needs three things that rarely coexist: frontier AI fluency, organizational familiarity, and modeling peer-to-peer apprenticeship.

Frontier AI fluency is built through the daily practice of assembling and fine-tuning the jigsaw as pieces shift. Organizational familiarity is built through understanding the organization’s tacit knowledge, its workflows, its political dynamics, its coordination layer that AI does not touch. Modeling peer-to-peer apprenticeship requires an abundance and growth mindset and the belief that personal mastery grows by sharing it widely.

The “jigsaw frontier translator” who assembles the puzzle for the team is performing a role that does not exist in any org chart today. The scarcity of this profile is a structural bottleneck. Organizations will need to design around it as they try to scale the translation before the AI overhang becomes insurmountable.

Translation is genuinely hard because our personal AI jigsaw is designed for our use cases and AI fluency level. It does not automatically translate to our team, because each person has different use cases and different fluency levels. Even within a team with roughly the same AI fluency and use cases, personal quirks matter. The quirks that make a system work for one user will create friction for anyone else.

When I tried to translate my jigsaw for a colleague, I did not start with the full Claude Cowork and Obsidian system. I started with Cowork and just the productivity plugin to keep things simple. They were genuinely excited when Cowork pulled their tasks from Outlook and Otter and showed them as a Kanban-style dashboard. But they struggled to use Cowork on their own because it was constantly updating, breaking, and requiring troubleshooting. The same colleague easily adapted Manus into their workflow because it felt like a mature, easy-to-use product.

The frontier AI tools need to become much easier to use before they are adopted widely. The gap between my ease with Cowork and their frustration with it was the translation problem made visible. That experience changed how I think about the jigsaw translator role. The bottleneck is not knowledge or willingness, but the steep learning curve of the tools in the AI jigsaw frontier. The hardest part of the jigsaw is not finding the right pieces. It is accepting that the puzzle looks different for every person who sits down to solve it.

Thank you for this, you’ve clarified so much of the current moment for me!